TRENDING: Sustainability and Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Industry

Having examined the concept of sustainability and the various reporting frameworks, it is reasonable and justifiable to be curious as it relates to Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. This piece seeks to break down this relationship with a throwback to where it all started – the history of the black gold in Nigeria.

Key facts on Nigeria’s oil and gas

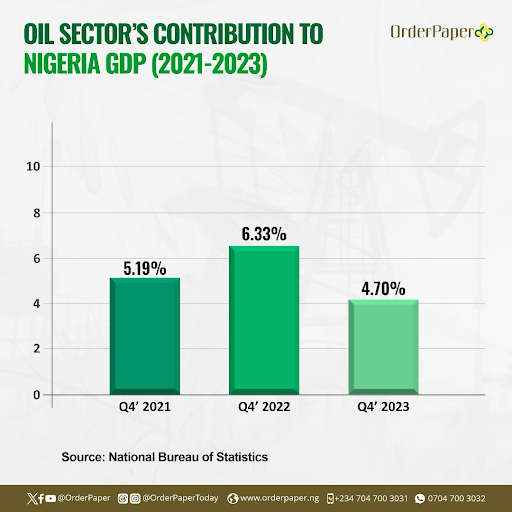

Nigeria is a nation rich in natural resources, particularly oil and gas. As of July 2023, Nigeria had a gas reserve of 208.83 trillion cubic feet which represents 33% of Africa’s total gas reserves of 620TCF and as of September 2023, Nigeria’s crude oil reserve stood at 36.9 billion barrels. The country’s oil and gas sector has played a pivotal role in its economic development and has been a significant contributor to its GDP over the years. (See infographic below)

However, the sector has also faced numerous challenges, including environmental degradation, social unrest, and issues related to transparency and accountability. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on sustainability reporting globally as a means to address these challenges and promote responsible practices within the industry.

Historical Evolution of Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Sector

The advent of the oil industry can be traced back to 1908, when a German entity, the Nigerian Bitumen Corporation, commenced exploration activities in the Araromi area, southwest of Nigeria. These pioneering efforts ended abruptly with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Oil prospecting efforts resumed in 1937 when Shell D’Arcy (the forerunner of Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria) was awarded the sole concessionary rights covering the whole territory of Nigeria. Their activities were also interrupted by the Second World War but resumed in 1947. Concerted efforts after several years and an investment of over N30 million, led to the first commercial discovery in 1956 at Oloibiri in the Niger Delta. This marked a significant turning point for the country’s economy, leading to a rapid expansion of the sector and attracting foreign investment from multinational oil companies.

As production increased, Nigeria became one of the largest oil producers in Africa and a key player in the global oil market. The revenues generated from oil exports fueled economic growth and development in the country, but they also created a dependence on oil as the main source of revenue, making the economy vulnerable to fluctuations in oil prices.

However, the rapid expansion of the oil and gas sector came at a cost. The Niger Delta Region, which is home to most of Nigeria’s oil reserves, suffered from widespread environmental degradation and biodiversity loss due to oil spills, gas flaring, and other forms of pollution. The defunct Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR), now Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), estimated that 1.89 million barrels of petroleum were spilled into the Niger Delta between 1976 and 1996 out of a total of 2.4 million barrels that spilled in 4,835 incidents (approximately 220 thousand cubic metres). It is pertinent to note here that the majority of oil spills occurring in the Niger Delta are considered ‘minor’ and so are not reported.

It is safe to say that this statistics is alarming for an area of only about 70,000 km2 in size.

Most of these oil-spill incidents reported in Nigeria occurred in the mangrove swamp forest of the Niger Delta region. Mangrove, of course, is one of the most productive ecosystems in the world with a rich community of fauna and flora — making the negative effects of the oil spills obvious.

The overall effects of oil spill on biota and ecosystem health are manifold. Oil extraction interferes with the functioning of various organ systems of plants and animals. It creates environmental conditions unfavourable for life; for example, oil on a water surface forms a layer which prevents oxygen penetration into water bodies, and this in turn leads to the suffocation of certain aquatic organisms. Crude oil contains toxic components, which cause outright mortality of plants and animals as well as other sublethal damage. The biodiversity loss is spiralling.

Additionally, the host communities in the region continued to feel marginalised, exploited and excluded from the benefits of oil extraction, leading to social unrest and conflicts with oil companies and the government. The social licence to operate has hardly ever been obtained.

In 2008, a ruptured Shell pipeline in the Bodo community of Ogoniland, Rivers State, caused two significant oil spills, resulting in extensive environmental damage and contamination of waterways, farmlands, and fishing grounds. The spills affected thousands of local residents, disrupted livelihoods, and caused severe ecological harm to the region. Despite the devastating impact on the community and ecosystem, Shell faced criticism for its response to the spills and the slow pace of cleanup efforts, raising concerns about the company’s accountability and the environmental damage caused by the crisis. This however did not stop business as usual nor the company from raking billions in revenues to shareholders who seem blind-sided by these heinous injustices done to an indigenous population in 2009 another spill occurred in Bomu, which is in the same local government as Bodo.

Furthermore, the casualization of labour by crude oil mining companies in the Niger Delta was also an issue of longstanding concern, with reports highlighting instances of exploitative working conditions masked by third party employment, inadequate wages, lack of job security, and limited access to basic labour rights.

These concerns heralded the enactment of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) 2021, repelling six laws – the Associated Gas Reinjection Act, the Hydrocarbon Oil Refineries Act, Motors Spirit Returns Act, Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (Projects) Act, Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Act, the Petroleum Products Pricing Regulatory Agency (Establishment) Act while two laws are to be subsequently repealed upon the happening of some events – the Petroleum Profit Tax Act, 2004 and the Deep Offshore and Inland Basin Production Sharing Contract Act, 2019.

The PIA addressed the host community issue by creating the Host Community Development Trust Fund (HCDTF) whose purpose is to foster sustainable prosperity, provide direct social and economic benefits from petroleum to host communities, and enhance peaceful and harmonious coexistence between licensees or lessees and host communities. Specifically, the law stipulates that existing host community projects must be transferred to the HCDTF, and each settlor (company or oil licence holder) must make an annual contribution of an amount equal to 3% of its operating expenditure for the relevant operations from the previous year. The Act further addressed other environmental issues such as gas flaring, hydrocarbon tax, amongst many other issues.

Importance of Sustainability Reporting in the Oil and Gas Sector

At the end of every extraction activity, the project ought to be decommissioned and abandoned to restore the site to a safe condition that minimises potential residual environmental impact and permits reinstatement of activities such as fishing and unimpeded navigation at the site. This act of restoration has always been one of the major clamours and a twin pillar of global environmental policy.

Amongst many other ills the PIA 2021 has come to correct, the ill of improper decommissioning is a major one. Even though the PIA now has express provisions for abandonment, decommissioning and disposal of oil and gas structures, there are still huge gaps in which sustainability reporting practice can help address.

In companies’ environmental stewardship obligations and actions, there are sustainability concerns. By including details on decommissioning plans, timelines, and environmental impact assessments in their sustainability reports, companies can now demonstrate transparency in their approach to addressing environmental responsibilities. Also, through this reporting, companies may build trust and dialogue with stakeholders, addressing concerns and garnering support for their decommissioning efforts.

Furthermore, companies who include information on regulatory obligations, compliance status, and adherence to industry standards in their reports, show their commitment to meeting legal requirements and upholding environmental best practices during decommissioning activities.

It is also worthy of note that by providing information on environmental monitoring, post-decommissioning site assessments, and ecosystem restoration efforts in their reports, companies can communicate the lasting benefits of their environmental stewardship and commitment to sustainable practices in the post-operational phase.

Conclusion

The historical evolution of Nigeria’s oil and gas sector reflects the significant role the industry has played in the country’s development. Sustainability reporting has the potential to drive positive change within the sector by promoting transparency, accountability, and responsible practices.

As Nigeria’s oil and gas sector continues to evolve, there is a growing need for companies to embrace sustainability reporting as a tool to enhance their environmental and social performance, engage with stakeholders, and build trust with the communities where they operate. By adopting robust sustainability reporting practices, oil and gas companies in Nigeria can contribute to sustainable development, mitigate risks, and create long-term value for their shareholders and society at large.

Apr 13, 2024 by Iseghohime Efe Esq.Other Articles

-

RemTrack Plog

Tinubu's ‘Green’ Mobility Directive: All You Need to Know About the Shift to CNG Vehicles

- RemTrack Plog

-

RemTrack Plog

ANALYSIS: Emerging Regulation of Sustainability Reporting in Nigeria

-

RemTrack Plog

INSIGHT: Sustainability as the New Deal for Companies and Communities

- RemTrack Plog

- RemTrack Plog